9.0 You Can't Have Money Without a Contract

Long live the Contracting Officer, they bestow the grace of green.

You Can't Have Money Without a Contract

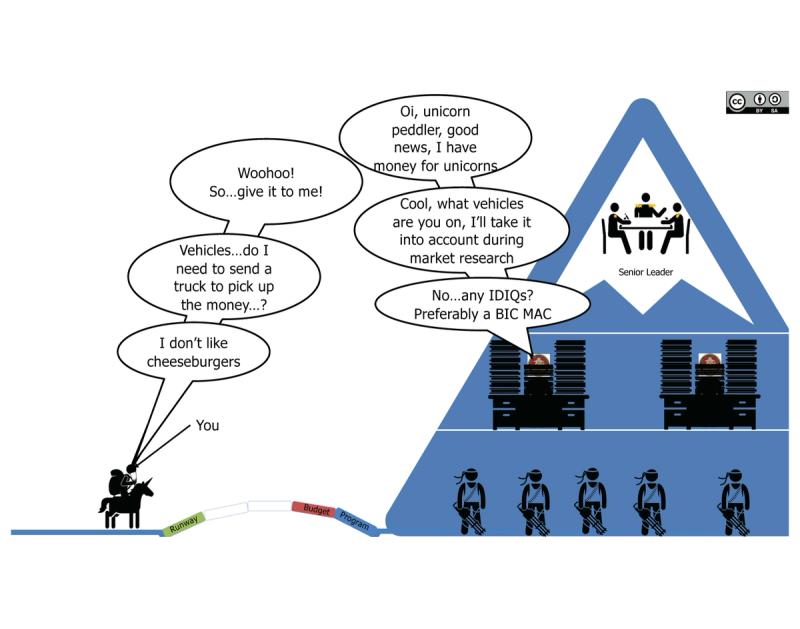

An often overlooked, misunderstood, bewildering and opaque art is that of the contract. Sure, everyone knows you NEED a contract, but there's just SO MANY ACRONYMS, and different kinds, and half of them seem worthless from the point of view of a company.

Nonetheless, functionally, the government CANNOT give your company money without a contract (or agreement).

To put a fine point on things, only career field 1102 contracting officers ("KO's" don't ask me why it's K and not C) with a contracting warrant are legally allowed to obligate the government. All others are just people who talk.

Now, we wont dive into the difference between a KO, COR, COTR, etc, let's just stick to contracts and follow the bouncing ball.

As we briefly described long ago in this guide, when a customer (program manager) wants to spend money to buy things for their users, they need a contract.

Some have strong preference of what vehicle, contract type, contract agent, etc, sort of like buying your toothpaste from Target vs. WalMart.

Some are required to use particular contracts per their organization's rules and regulations. These are all things you should figure out.

The bottom line is that PMs are not necessarily paired or assigned 1-to-1 with a KO who's job it is to buy their stuff.

Remember, the PM has the money in their Program Elements for THEIR programs, they may very well use any number of contracts to buy the things they want.

Important point here: smart companies bring work from customers to contracts. If you have a customer (PM) who wants to buy your things, and you're on contract vehicle A but not vehicle B, often times you can convince the PM to buy the things through vehicle A.

Remember the golden rule.

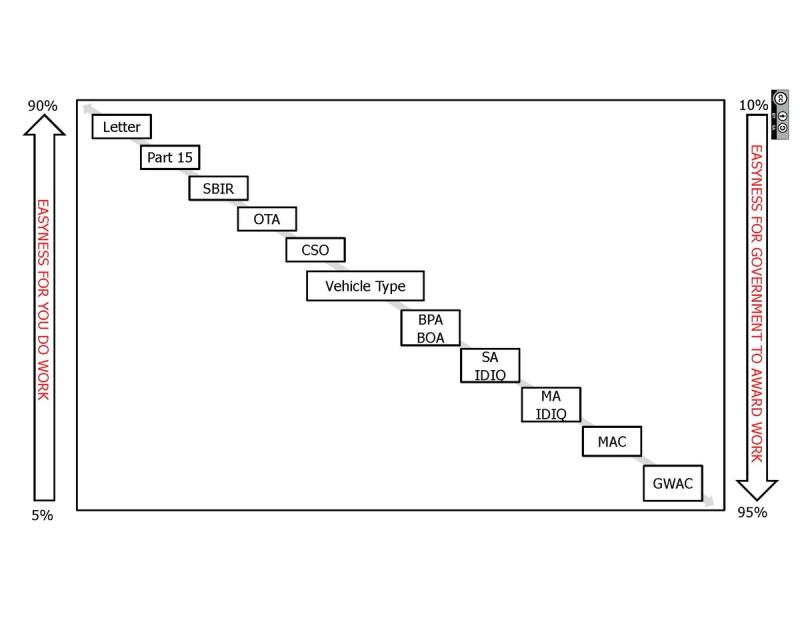

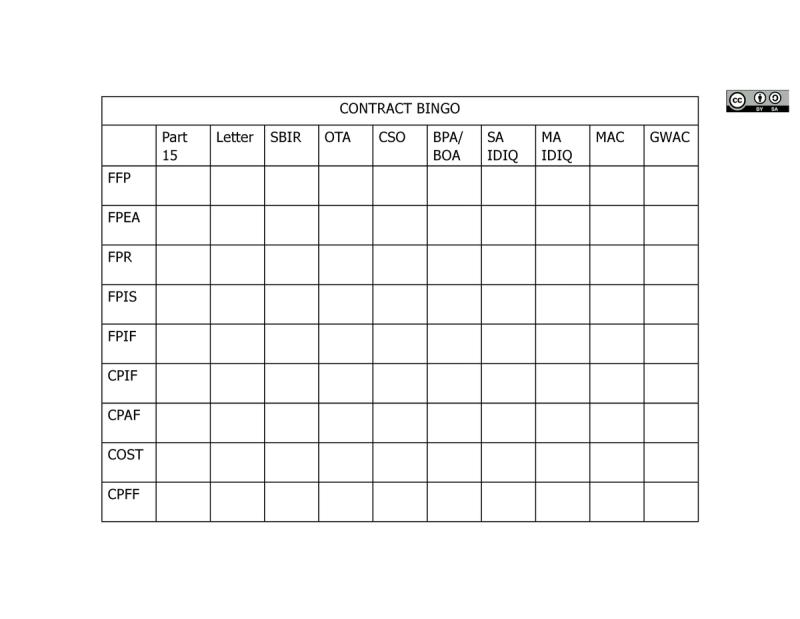

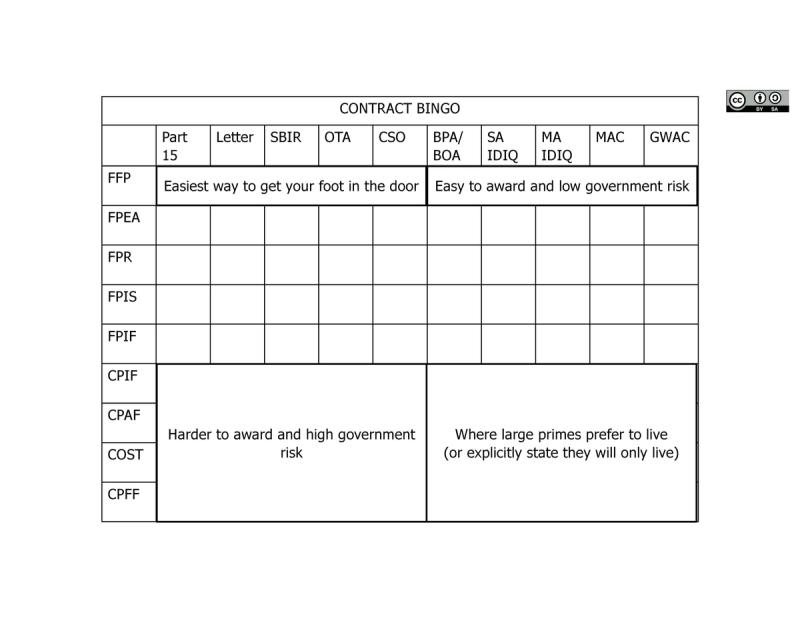

Now, there are a lot of contract "vehicle" types. Some are easier than others to award work on.

All the way at the top is a FAR Part 15 negotiated contract, legit a document written just for you to buy stuff just from you.

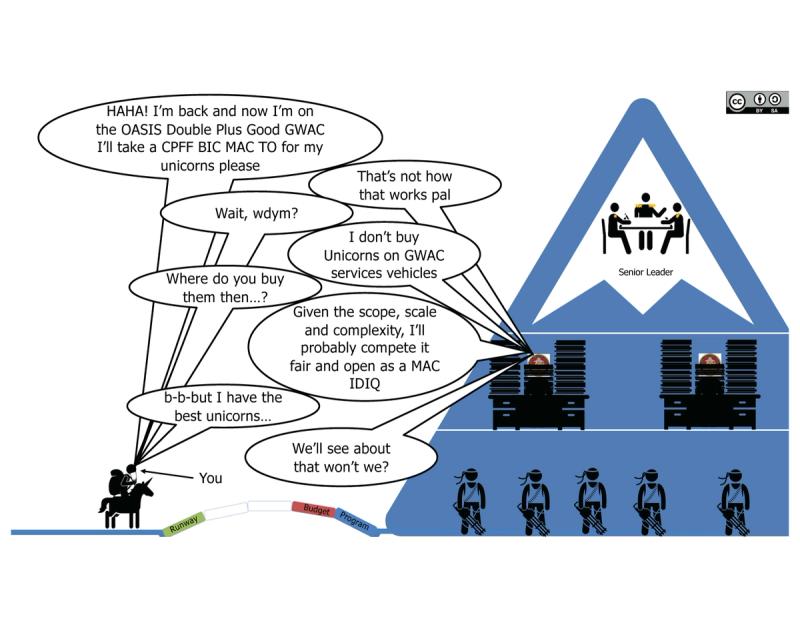

On the other end of the buying spectrum is a Government-Wide Acquisition Contract (GWAC) or Multiple-Agency Contract (MAC) like OASIS+, PACTS IV, NASA SOUP 6, etc.

These contracts are with 10's to 1,000's of companies, and are not really money-producing contracts per se.

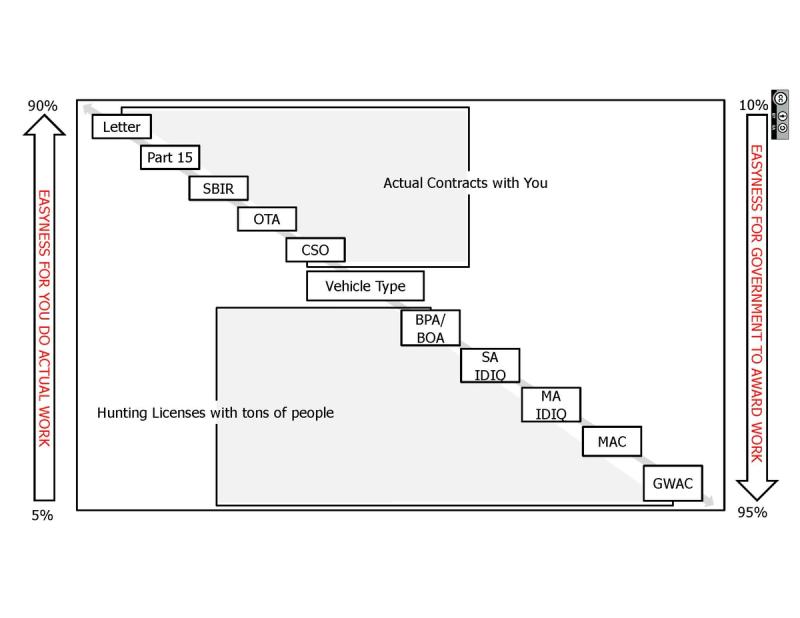

Things like Blanket Purchase agreement, Indefinite Quantity/Indefinite Delivery, Multiple Award Schedules, etc are just "hunting licenses" for winning work. Just like if you manage to get your product listed on Amazon, you don't magically make sales. That means you have to invest blood, sweat and tears to "get on" the vehicle, and then you have to spend even more blood sweat and tears to actually win a money-producing task/delivery order.

Task order: an actual award to buy services on an IDIQ

Delivery order: an actual award to buy products on an IDIQ

Fun times...

But why?

Because those large IDIQ, MAC, GWAC contracts are easier.

Think about it, it's like having certified vendors for particular goods and services. the based contract vehicle competition takes care of baseline things like past performance, certifications, and in some cases prices.

I liken this to online shopping, I love buying things from Amazon, and I'm somewhat annoyed when a company doesn't sell l their things on Amazon. I have to go to their website, enter all of my address and credit card information, and worst of all, deal with their shipping timelines. I just want to swipe the buy button and know I'm going to get my protein shakes in 24-48 hours. That's sort of the difference between FAR Part 15 contracts and multiple award contracts.

So, when a PM wants to buy something, all the have to do is write the requirement, put it out for bid on the vehicle, and they know that everyone who responds has a certain baseline of capability, reliability, and affordability.

That vs. a FAR Part 15 contract where they have to cast their requirement into the wide open and take their chances with who will respond and then do all their own due diligence on the proposals.

Do you like picking through all of the reviews on Amazon, or do you just go to the "suggested by Amazon" products because you know they'll be mostly reliable? It's kind of like that.

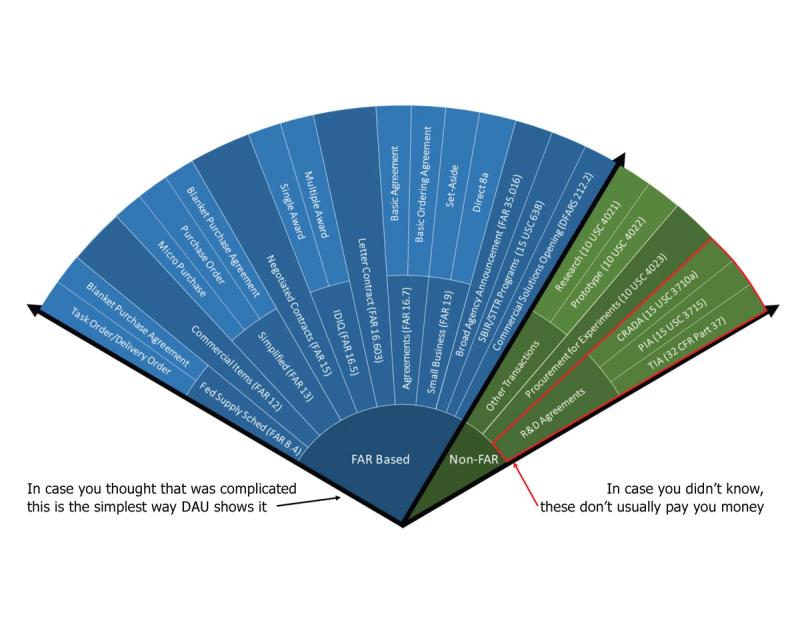

Now let's get the nitty details out of the way about ALL of the various DoD contract vehicle types...

Different vehicles are often used for different things, so knowing the difference can help you target which vehicles you'd like to be on.

- Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA): Think of a BPA as a charge account that the federal government sets up with trusted suppliers. It's used to fill anticipated, repetitive needs for supplies or services. Instead of processing a full purchase each time, the government can quickly order against this account, which streamlines frequent, smaller buys.

- Purchase Order: This is a basic contract where the government orders goods or services from a supplier at a set price. It's the equivalent of a standard shopping transaction but in a formal contract form.

- Micro-purchase: These are small dollar purchases that don't exceed a certain threshold (usually a few thousand dollars). They're made without obtaining competitive quotes, aiming to reduce administrative costs and increase efficiency.

- Task Order/Delivery Order: When the government knows it will need batches of supplies or services over time but can't determine the exact quantities, it issues these orders. They are placed against an existing contract, specifying what's needed at a particular time.

- Commercial Items (FAR Part 12): This type of contract is for buying things that are already available in the commercial market. The idea is to get what the military needs without reinventing the wheel, saving time and resources by acquiring off-the-shelf goods or services.

- Basic Ordering Agreement (BOA): A BOA is not a contract itself but an understanding between an agency and a supplier. It sets terms and prices for future contracts, making the actual contract execution faster and smoother.

- Letter Contract (FAR 16.603): This is a temporary contract that lets the contractor begin work immediately before the formal contract is finalized. It's like a "we'll pay you, start working now and we'll sort out the details later" arrangement.

- Agreements (FAR Part 16): These are varied arrangements that can be put in place for special working relationships or partnerships, like when companies team up to work on a government project.

- Small Business Set-Aside (FAR Part 19): These contracts are reserved exclusively for small businesses. It's a way for the government to support small companies by giving them a fair chance to compete for contracts.

- Negotiated Contract (FAR Part 15): Unlike buying something off a shelf, some military needs are so unique that they require back-and-forth negotiation to settle the terms and prices. These contracts result from that negotiation.

- Simplified Acquisition (FAR Part 13): This method is for purchasing lower-value items. It's a faster, easier process for the government to buy what it needs while keeping the paperwork to a minimum.

- Other Transactions (OTs) for R&D and Prototypes (10 U.S.C. 2371, 2371b): These are more flexible arrangements that the government uses when it needs cutting-edge research and development, including prototypes. OTs are unique in that they are not subject to many of the regulations that govern standard government contracts.

- Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO): A CSO is a modern approach for procuring innovative commercial products, technologies, or services that meet the government's needs, often with more relaxed rules to encourage non-traditional contractors to propose creative solutions.

- Research and Prototype Contracts: These contracts focus specifically on the exploration and initial development of new technologies, systems, or materials that the military could use.

- Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA): Under a CRADA, the government and private companies or academia can legally collaborate on research and development projects, sharing resources, knowledge, and expertise.

- Partnership Intermediary Agreements (PIA): These agreements aim to create partnerships between the DoD and intermediaries like universities or non-profits to facilitate technology transfers and support defense objectives.

- Technology Investment Agreements (TIA): TIAs help the government invest in advanced technologies. They're used to attract and involve commercial firms in military research and development efforts, with a particular interest in innovative technologies not usually developed under traditional defense contracts.

Ok, so that's all the types of contract vehicles, but there's also a ton of different ways that those contracts treat prices and costs.

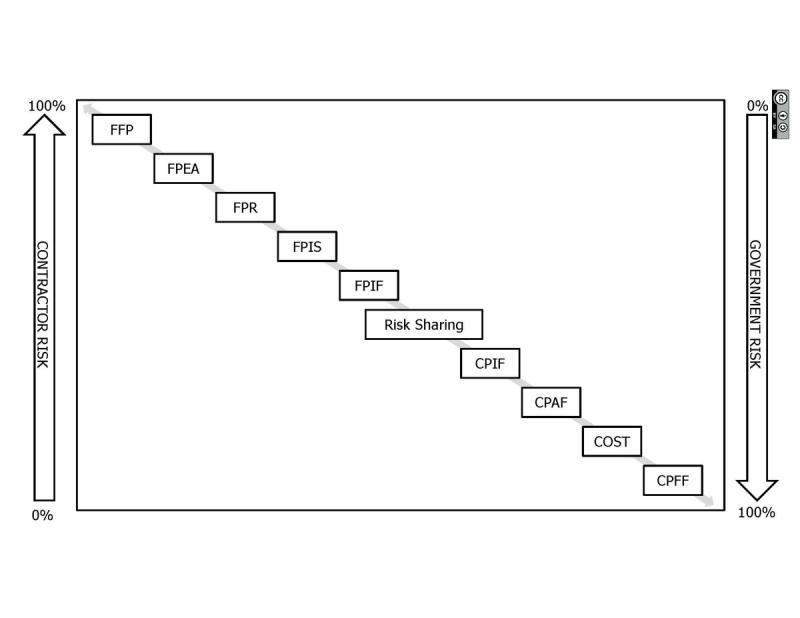

And the major difference is all about risk.

- FFP (Firm Fixed Price): The contractor agrees to deliver a product or service at a set price.

- Government risk: Low, as the cost is fixed.

- Contractor risk: High, as they bear any cost overruns.

- FPEA (Fixed Price with Economic Price Adjustment): Similar to FFP, but includes provisions for adjusting the contract price due to specific economic conditions.

- Government risk: Moderate, as adjustments can increase costs.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, as it allows for some cost fluctuation coverage.

- FPR (Fixed Price Redeterminable): The price is initially fixed but may be adjusted based on certain conditions defined in the contract. This type isn't standard and might be less commonly referenced, potentially being confused with other fixed-price variations.

- Government risk: Moderate, due to potential adjustments.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, as it offers a mechanism to adjust the contract price under specified conditions.

- FPIS (Fixed Price Incentive Fee): A fixed-price contract that provides for adjusting profit and establishing the final contract price through a formula based on the relationship of total allowable costs to total target costs.

- Government risk: Moderate, as costs can increase if targets are met.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, incentivizes cost control and efficiency.

- FPIF (Fixed Price Incentive Firm): Similar to FPIS, it's a fixed-price contract that includes a formula for final price determination that incentivizes performance on the contractor’s part.

- Government risk: Moderate, as incentives can increase total cost.

- Contractor risk: Moderate, with potential for higher profit if performance targets are met.

- CPIF (Cost Plus Incentive Fee): The contractor is reimbursed for all allowable costs as determined by the contract plus an incentive fee based upon achieving certain performance objectives.

- Government risk: High, as costs can escalate.

- Contractor risk: Low, since costs are covered, plus an incentive for efficiency.

- CPAF (Cost Plus Award Fee): Reimburses the contractor for allowable costs and includes a fee consisting of a base amount fixed at inception and an award amount, given for meeting or exceeding certain performance criteria.

- Government risk: High, as costs can escalate, but controlled by performance criteria.

- Contractor risk: Low, with incentives for performance.

- COST (Cost Contract): A cost-reimbursement contract in which the contractor receives no fee.

- Government risk: High, as all costs are covered without direct profit for the contractor.

- Contractor risk: Low, but lacks incentive for efficiency since there's no profit.

- CPFF (Cost Plus Fixed Fee): The contractor is reimbursed for all allowable costs plus a fixed fee which is agreed upon at the contract's inception.

- Government risk: High, as costs can escalate.

- Contractor risk: Low, as all costs are covered plus a guaranteed fee.

In general terms, the most common contract types are FFP and CPFF.

With the former, the contractor eats all the risk.

With the latter, the government eats all the risk.

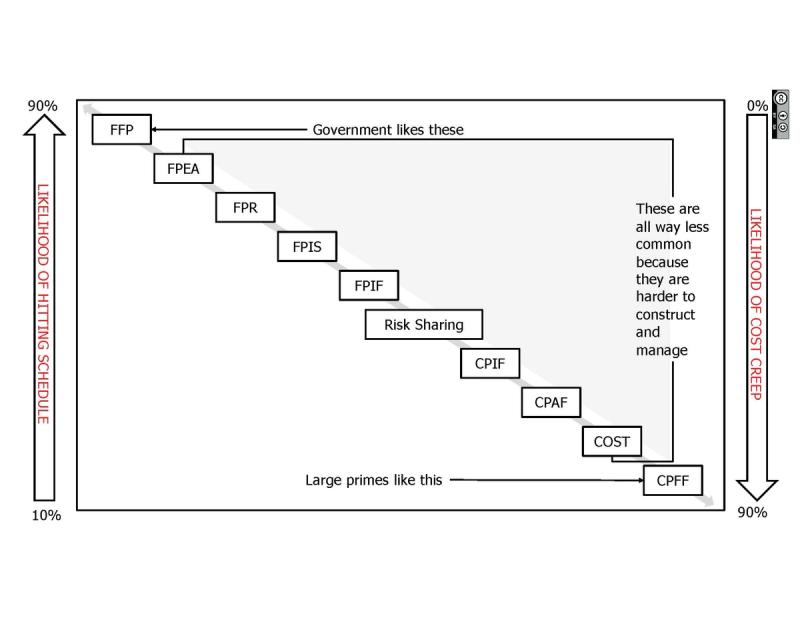

Now there is a lot of talk about fixed-price vs. cost-type contracts these days, the big primes are saying they wont even bid on FFP development contracts. Meanwhile the government is very frustrated with cost-type contracts, particularly for large weapons systems that are never on time of budget.

We'll talk a little about why this happens all the time in another segment.

Just take it for granted that cost-type contracts seldom deliver on time and on budget, but hoinestly that's basically what they're for.

Now, you can sort of mix and match most vehicle types with most price/cost types, though most vehicles only allow for certain types of cost/price structures, so do your homework.

You could easily have a Firm Fixed Price Task Order and a separate CPFF Task Order on the same contract, it's up to the PM and the KO to determine how they want to do it.

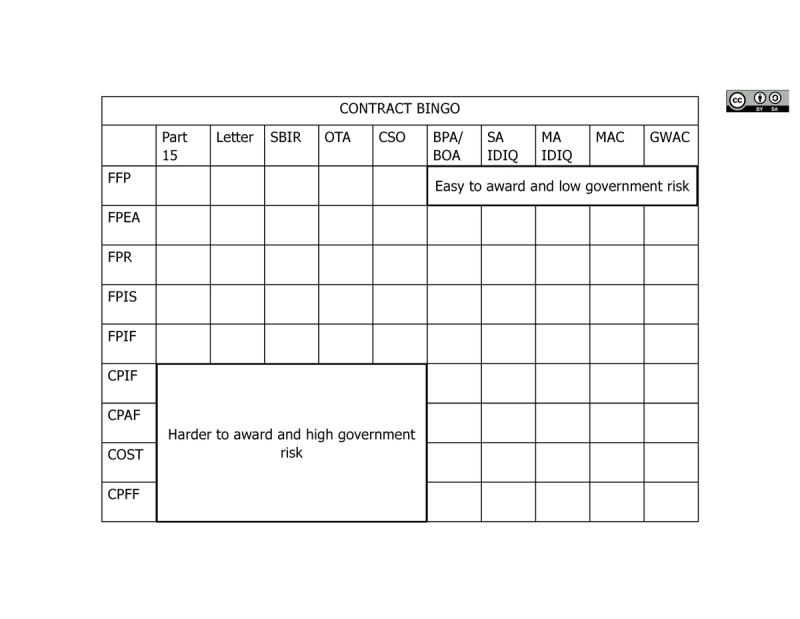

Logically, the multiple award and IDIQ contracts are easier for KOs to award, and FFP is the lowest risk.

On the other end, singular contracts of a cost-type are a whole lot more work and much higher risk.

See how we're sort of making an easy/risky matrix here...

So, if you're trying to get your foot in the door, FFP contracts may be the easiest route.

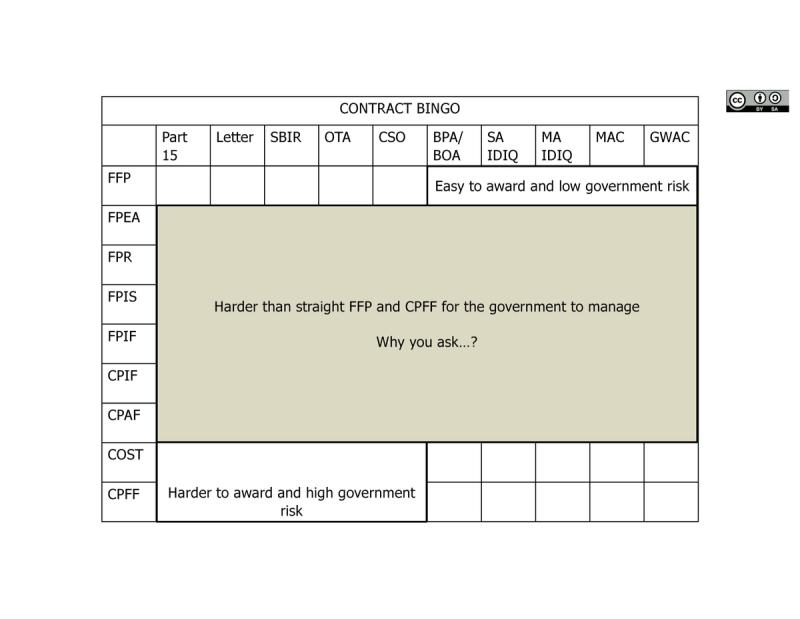

Incentive contracts seem like a great idea, align the profit motive of the contractor with the delivery objective of the government.

However, anything that involves calculating incentives, the government generally avoids having to do, because it's a lot of work and there's often hurt feelings with the contractor when you tell them that their fee is cut for not delivering on time.

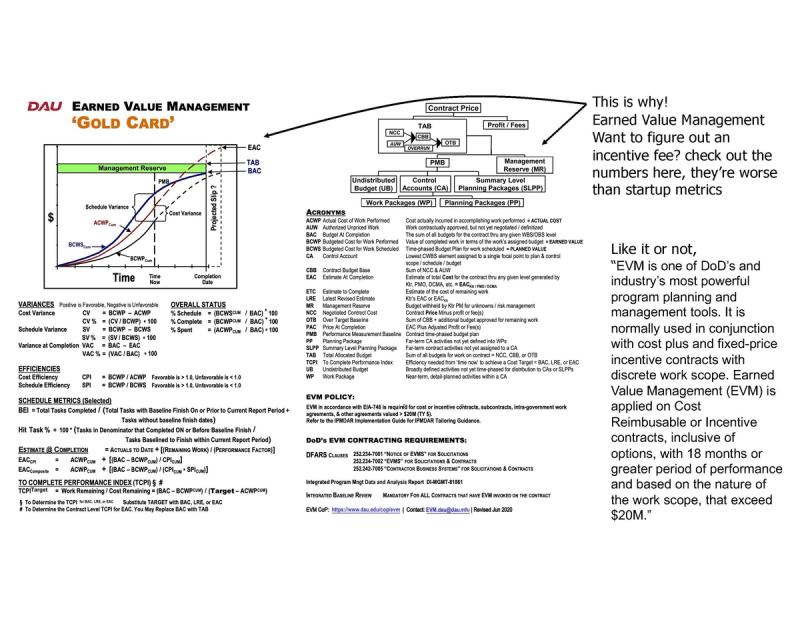

And why are they complicated? Earn Value Management!

EVM is almost only used on very large multi-million/billion dollar systems contracts. It's a very logical system, it's just one extra thing to argue over.

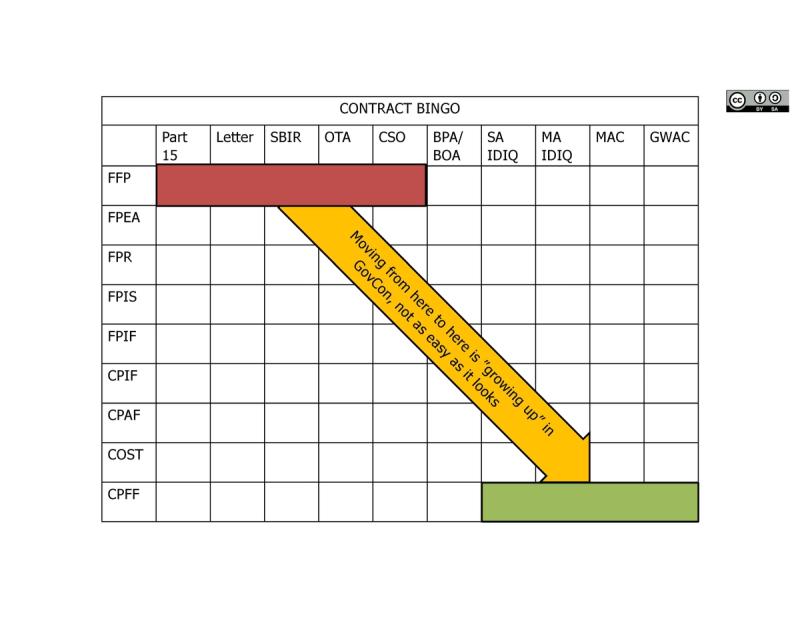

Now, down to brass tacks.

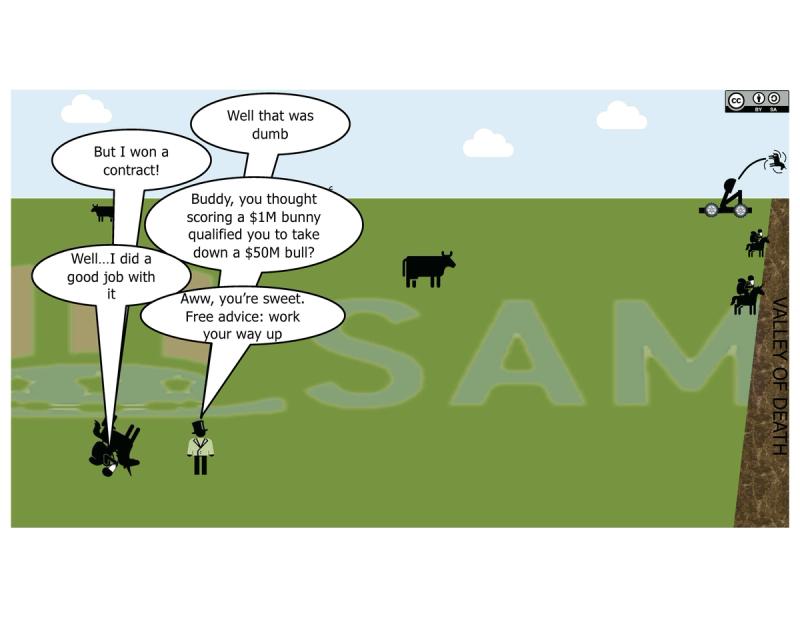

If you're new to the game, you're probably going to have to start in the "hard to award" contract vehicle type with a firm fixed price structure.

As you mature, you'll want to shift to the other end of the matrix, to the easy to award cost-type structures.

If you don't see why, this may not be the game for you.

Newbie question: "But why can't I just skip to the end and win the MAC IDIQ CPFF contracts?"

Sage answer: "Because no one trusts you"

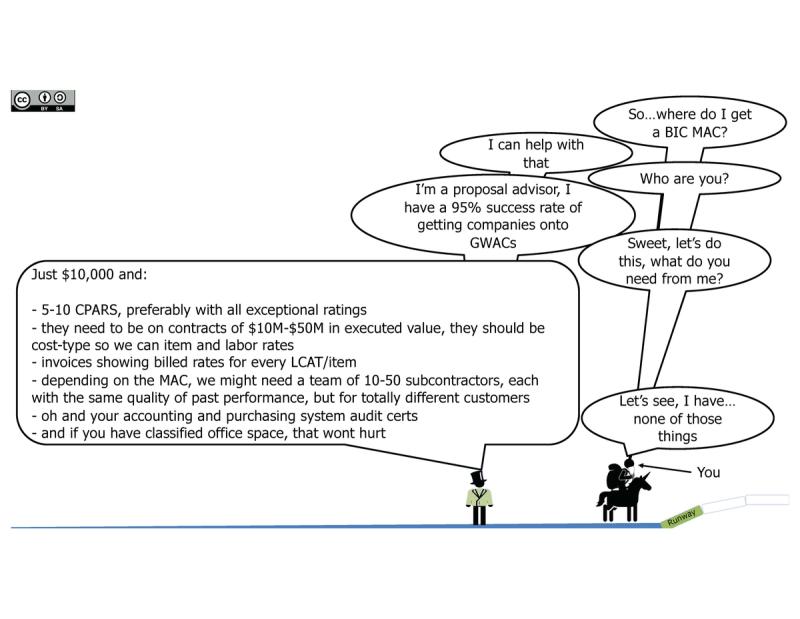

There are of course consultant to help you get contracts, many of them do a great job.

In GovCon there's basically a consultant for everything.

You can pay with time or you pay with money, either way you'll pay to win.

But to win a base award on an IDIQ you usually need GOOD, PRIME past performance (look up CPARS) that is RECENT (last 3-5 years) and relevant (is of a similar "scope and scale"), along with a varied list of GovCon merit badges (more on those later).

If you're new to the game, you won't have these items.

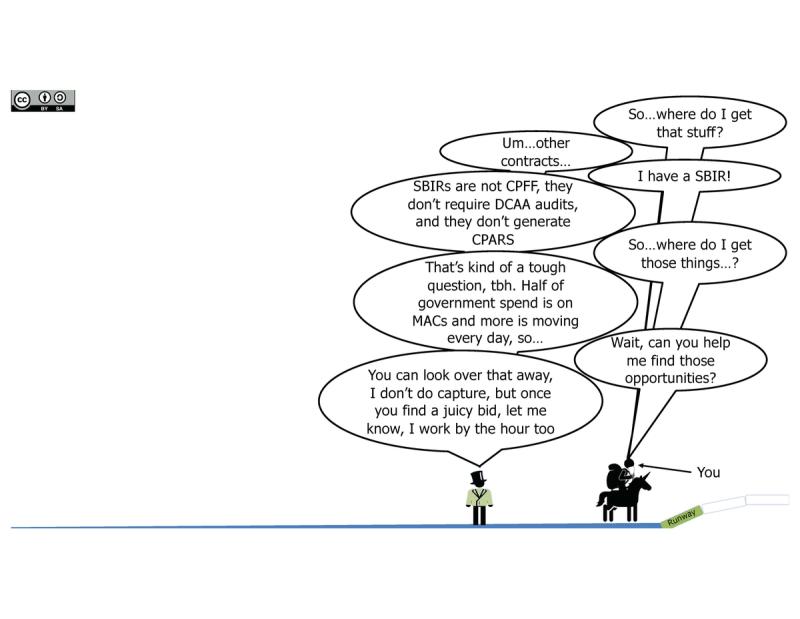

To make things more difficult, subcontract past performance usually isn't relevant(for good reason), and those wonderful SBIRs and OTAs that are such awesome ways to quickly get your technology funded and prototypes fielded...

They don't get CPARS.

And most of them are not of a relevant scope and scale for the major IDIQs.

So what does one do?

How does one get this critical past performance?

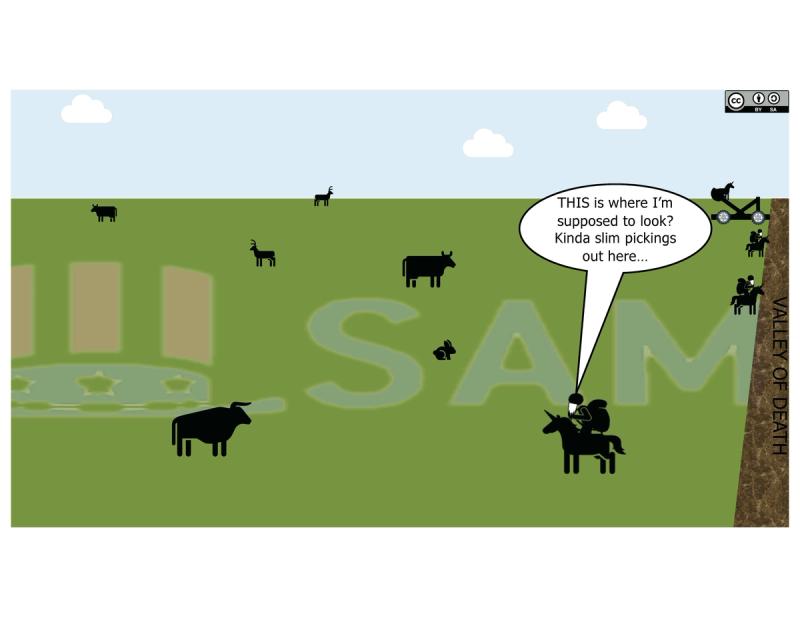

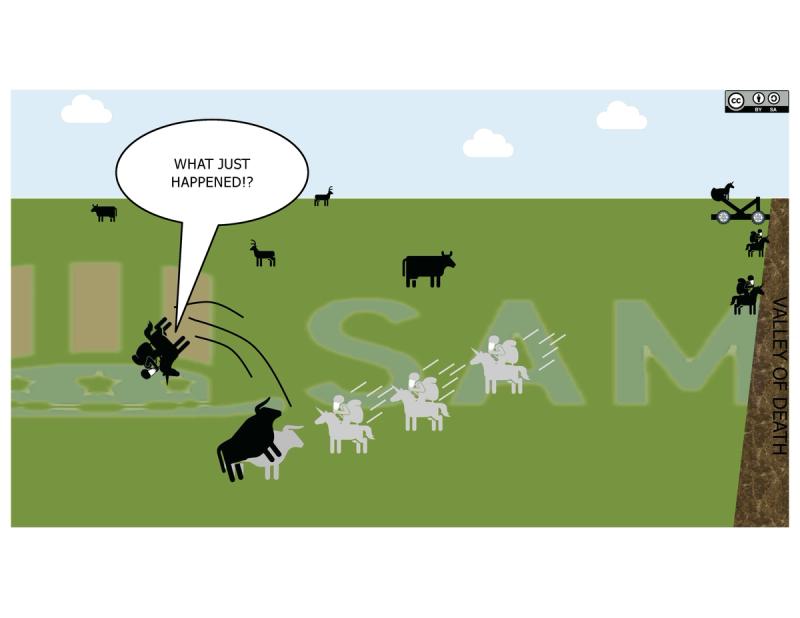

You go out to the plains and go hunting for opportunities.

Now keep in mind that only about 50% of opportunities are listed on SAM.gov, the rest are on those IDIQ vehicles.

That said, you can and will find opportunities out there.

It's your job to go get 'em.

Winning these contracts out in the wide prairies of GovCon is one of the few ways to build up your past performance.

Now, again, trying to skip to the end is almost always a bad idea.

You will likely want to work your way up the food chain.

Trying to jump from a small prototype or delivery contract in the single-digit millions to one that's 10's of millions is quite a leap.

Again, why would any customer trust you to suddenly have the capacity to deliver on a $50M contract when you've only ever delivered on a $5M contract?

Major subs is a way to square that, but we won't get into that here.

When you're working your way up, try thinking about contract sizes in this rough scale:

>1M

1M-5M

5M-10M

10M-25M

25M-50M

50M-100M

100M-250M

Mind you that's executed value, not ceiling or potential value. No one cares how high the contract ceiling is, only the obligated and expended amount.

Headlines that read "<contractor X> won a contract with a potential value of Y" 9 times out of 10 it's either an IDIQ that means almost nothing, or that's the contract ceiling and means slightly more than nothing.

Ceiling: the limit of dollars that can be awarded on a contract

Obligated: dollars actually awarded on a contract

Expended: obligated dollars that are actually invoiced

Expended will be a fraction of the obligated will be a fraction of the ceiling

Bottom line: don't build yourself a reputation for making wild and unwise bids, it's both a waste of time and will likely turn off customers.

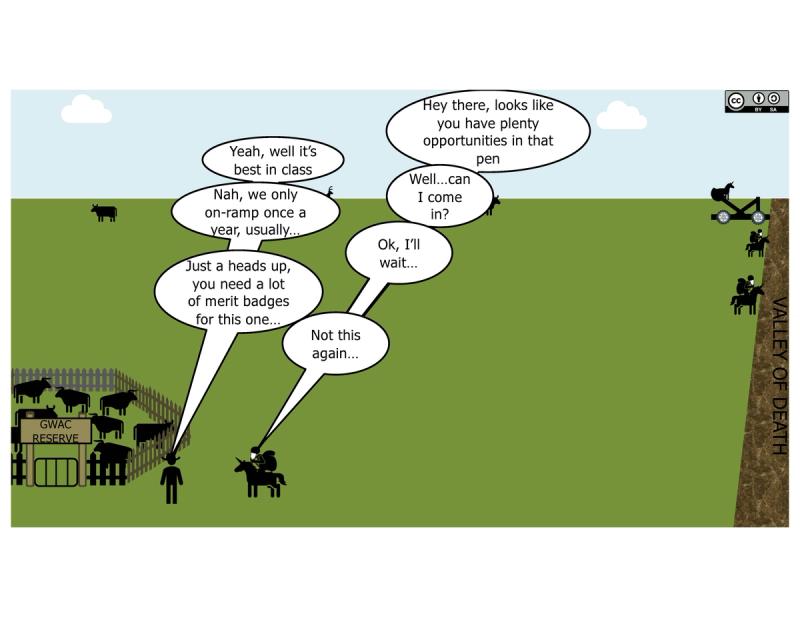

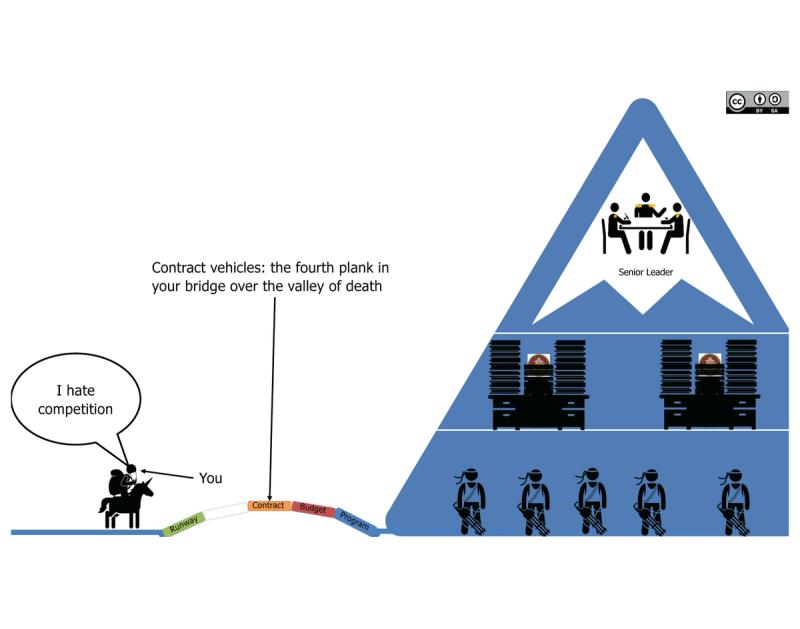

Now, once you work your way up the chain, you may want to go after one of those great Indefinite Delivery contracts.

After all, that's where all the big healthy opportunities are penned up, here's some things to know:

- There are agency-only IDIQs, like DARPA's TASS, that have multiple vendors but only serve one organization.

- There are Service specific IDIQs, like the Army's CHESS for IT stuff that anyone in that Service can (and often are required to) order from

- There are contracts run by organizations that anyone can order from, like EWAAC in the Air Force

- There are multi-agency contracts (MACs) that multiple agencies can order from.

- There are government-wide contracts run by GSA that ANYONE can order form

- Most large IDIQ's have on-ramp periods, every year or two, where they bring on new awardees.

- If you want to on-ramp onto one of these contracts, it pays to prepare well ahead of time, everyone else does.

It's your job to figure out which vehicles are best for your target customers and your product or service.

Because, if you don't you might do what so many companies do; go get on a bunch of irrelevant vehicles that do nothing for your customer.

And staying on vehicles is not a one-and-done prospect, once you get on the vehicle, you have STAY on the vehicle, which often means you have to win, or at least bid on task/delivery orders, or else they'll off-ramp you.

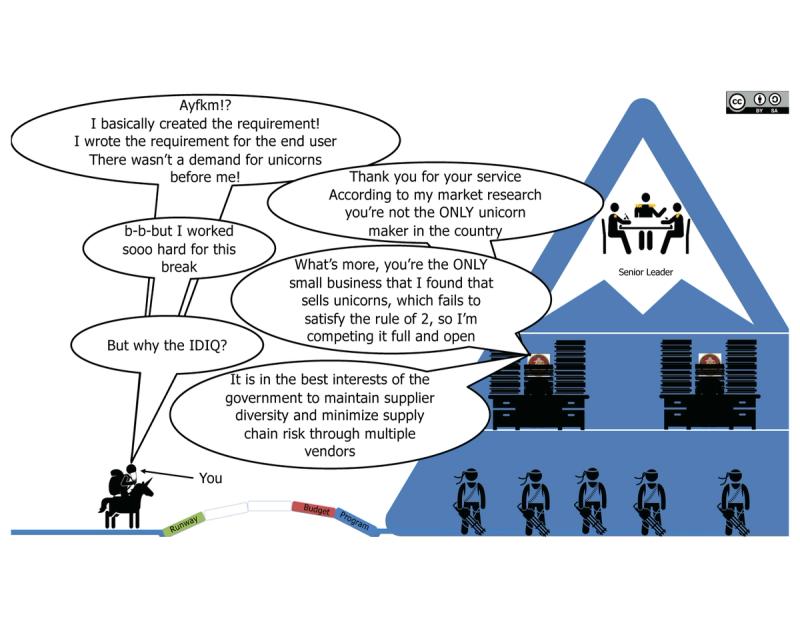

Now, keep in mind, even if you do ALL OF THE WORK, creating a requirements with end users, working it up to the customer, getting them to put in in their budget and then put out a contract to buy it, 99% of the time you will still have to COMPETE for it.

Sorry, that's called equality of opportunity, don't like it, move to Russia.

Newbie question: "but what about sole source?"

Sage answer: "yes let's

Sole source contract happen, sure. But they're hard to pull off and undergo thorough scrutiny (unless you're an 8(a)).

You may think that your things is so special and unique that it justifies a sole source contract.

But, remember that requirements are DESCRIPTIVE not PRESCRIPTIVE, so describe your thing in words, then see if anyone else describes their thing in a similar fashion. If so, then good luck with a sole source.

To put a fine point on it, in order to award a sole source contract, the KO has to write a justification (J&A) that has to be blessed by the lawyers as satisfying one or more of hte following criteria:

Here's the concise list of the specific circumstances under which the U.S. Department of Defense may limit competition in contracting due to various justifications:

- Only One Responsible Source [FAR 6.302-1]

For continuation of a project with a major system or specialized equipment.

When awarding to another source would cause substantial duplication of cost or unacceptable delays.

When unique items are available from a single source or limited sources. - Unusual and Compelling Urgency [FAR 6.302-2]

Emergencies requiring immediate action to prevent significant financial or operational detriment. - Industrial Mobilization [FAR 6.302-3]

To maintain necessary facilities or suppliers in case of national emergency.

To retain services of experts for anticipated litigation.

To preserve critical research, engineering, or developmental capabilities. - International Agreement [FAR 6.302-4]

When a foreign government reimburses the acquisition and dictates the source.

When an international treaty or agreement specifies the solicitation source - Authorized or Required by Statute [FAR 6.302-5]

When law directs procurement from a specific agency or source.

For brand-name items intended for authorized resale. - National Security [FAR 6.302-6]

When revealing the government’s needs could compromise national security. - Public Interest [FAR 6.302-7]

When the head of the agency determines that open competition is not in the public interest for a particular acquisition.

So yeah, good luck with that.

At the end of the day, if you want to get paid, you need to figure out the contracts through which you customer can and will spend their money.

This takes research and probably conversations.

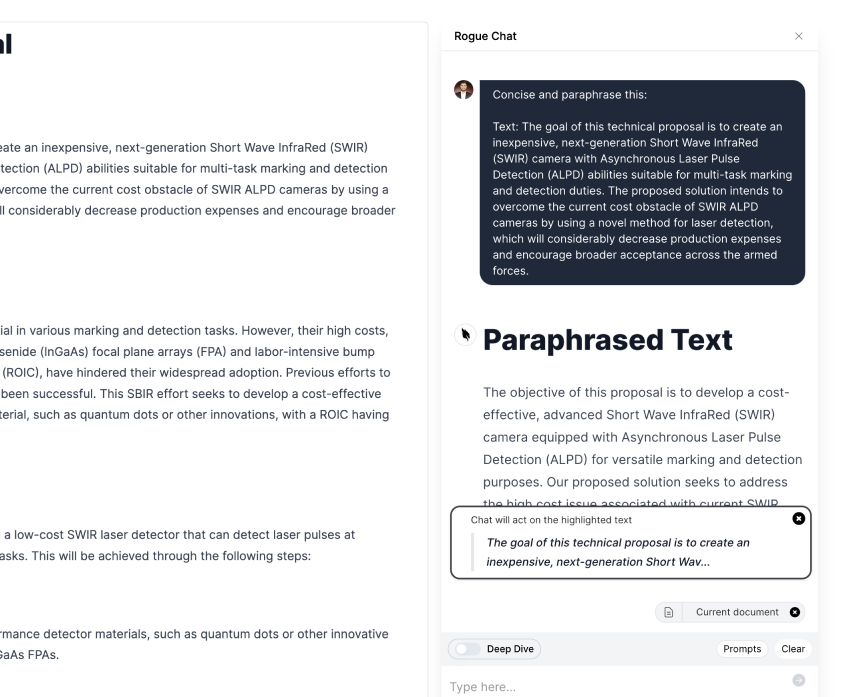

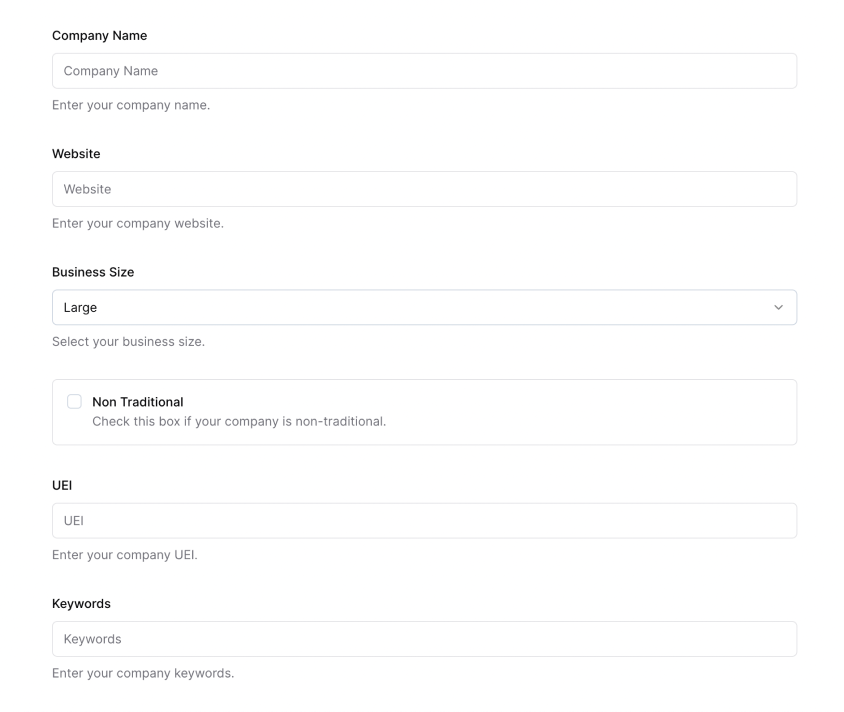

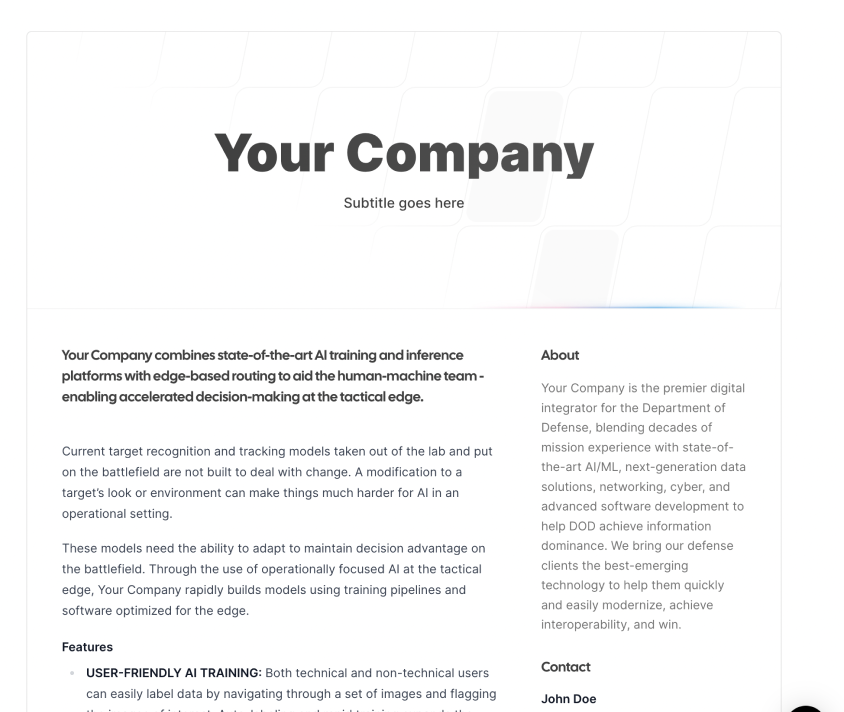

Sign up for Rogue today!

Get started with Rogue and experience the best proposal writing tool in the industry.